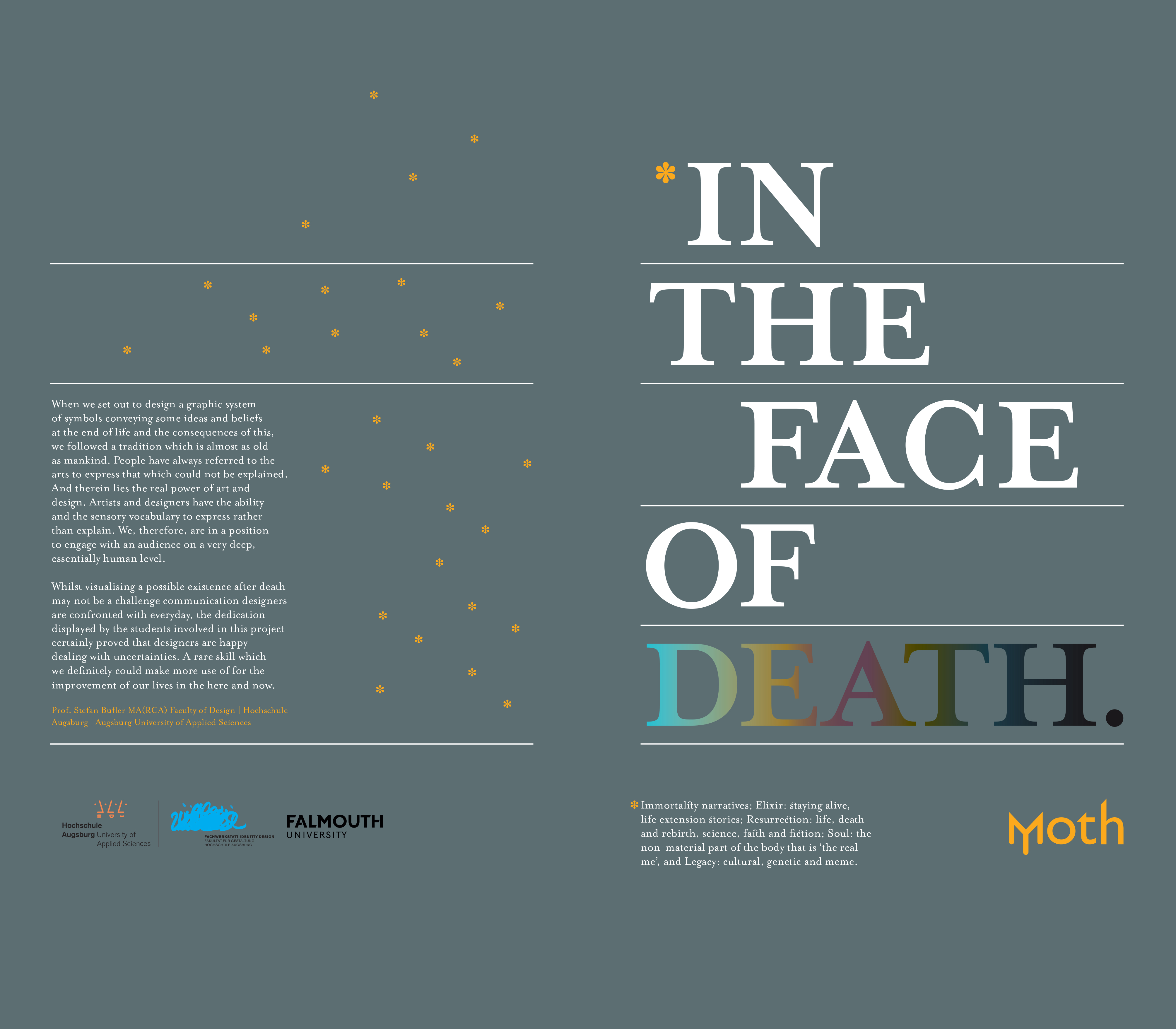

In The Face of Death

Publication designed by MOTH

Publication contributor:

Elixir | Resurrection | Soul | Legacy

By Stephen Cave

Publication contributor:

Elixir | Resurrection | Soul | Legacy

By Stephen Cave

Elixir

We humans are the true mortals. Simpler, smaller-brained creatures are free of death — not because the Reaper will spare them, but because they do not have to live with the knowledge that he won’t. They live in joyful ignorance of the inevitable. Once the shark has passed, the fish is free of fear, for a while at least. But we are never free of the knowledge that all this will end.

Today more than ever, we are each our own greatest project: we self-actualise, self-fulfil, self-express. And what happens when time is up? Are prizes handed out and grades awarded for the most actualised self? No, the entries are all torn to pieces, whether masterpiece or scribble. No wonder then that we dream of holding ourselves together, of fighting back the dissolution brought by time, of stopping the decay and disappearance of all that we have striven to be.

It might seem mad to think we can stop Nature’s law in this way. But to some, the opposite seems madder still: that all of this hope, wonder, memory and becoming will simply cease. And so the dream of an elixir that can preserve and prolong life is something close to a human universal, found in cultures across time and place. Stay alive, this dream whispers, day by day, and the years will take care of themselves.

Resurrection

In our struggle with the prospect of death, we seek sense-giving images from the world around us. “Do dead people come back again in the spring like flowers?” three-year-old Jane asked her mother. Well, Jane, wait until spring and we’ll see.

In nature, dying is not the end, but only part of a greater cycle — a cycle of life, death and rebirth. In contrast, a human life is linear: it progresses from birth through accretion then diminution into death and… that is it. The dead do not burst forth from the earth like March bluebells. At least, not when left to their own devices. But perhaps, we think, with a little help, these corpses can indeed be coaxed from the grave.

Magic, religion and science have long been united in the aim of transmuting the linear into the cyclical: transmuting that which is done and dust into that which re-forms and is re-done. So world religions are populated with dyingand- rising gods, from Osiris to Jesus, who serve as pioneers; who pass on to us the rituals — mummification, holy communion, cryonic freezing — that are to liberate us from linearity, that we might live again.

This is the hope of resurrection; a hope as humble as a bluebell and as grandiose as the gods.

Soul

It cannot be seen, or touched, or felt or smelt. It is undetectable, both in theory and practice. But we believe in it anyway. Even in our increasingly secular age, the vast majority of people on earth think they have a spiritual inner self. Few people, it seems, are happy to be soulless.

Perhaps it is because our bodies alone hardly seem adequate for the job of being human: messy and squelchy, prone to breakdown and destined for dissolution. How much better to believe that our real nature is something intrinsically indestructible, pure and immortal — a spark of the divine. When the body is lowered into the earth, we hope the soul will at the same time soar into the sky.

Of all the immortality beliefs, the soul most neatly answers the paradox at the heart of our view of death. On the one hand, we see that all things die and realise that we must too. But on the other hand, we cannot conceive of what this implies — our own non-existence; by simply trying to imagine the world without us, we conjure ourselves into being as the observing I/eye. And so death seems both inevitable and impossible. But for the ensouled, this is no problem at all: it is only my body that dies; I, the soul, fly free and forever. And so the paradox is resolved, and eternity ours. Or so the story goes.

Legacy

Most people fade from memory faster than we like to think: do you know the names of your eight great-grandparents? Only three generations gone and they have already evanesced like summer dew.

But this is not everybody’s fate. When Brad Pitt stormed the beach in the film Troy, clad in Achilles’ helmet and greaves, he was enacting his role’s greatest wish: everlasting glory. Achilles knew — because it had been prophesied — that if he stayed for the siege he would die, but that he would win undying fame. And so he stayed and fought and died and lives on. Ancient Greek warriors, like Hollywood actors, were in the immortality business.

But what life has Achilles won? Is he less dead because you are now reading his name? Less dead for all the films and statues he inspired? Or are those young men less dead whom he in turn inspired? Those who read as boys of the heroes of Troy and the glory of falling in a foreign field.

Homer, who in the Iliad granted Achilles his second life, later mocked it in the Odyssey. The hero Odysseus visits his old friend in Hades, only to be shocked by Achilles’s account of the dreary afterlife. Odysseus remonstrates — surely you, most renowned of all warriors, cannot regret having sacrificed long life for glory? Achilles replies, “I would rather work the soil as a serf to some landless impoverished peasant than be King of all these lifeless dead.”

We humans are the true mortals. Simpler, smaller-brained creatures are free of death — not because the Reaper will spare them, but because they do not have to live with the knowledge that he won’t. They live in joyful ignorance of the inevitable. Once the shark has passed, the fish is free of fear, for a while at least. But we are never free of the knowledge that all this will end.

Today more than ever, we are each our own greatest project: we self-actualise, self-fulfil, self-express. And what happens when time is up? Are prizes handed out and grades awarded for the most actualised self? No, the entries are all torn to pieces, whether masterpiece or scribble. No wonder then that we dream of holding ourselves together, of fighting back the dissolution brought by time, of stopping the decay and disappearance of all that we have striven to be.

It might seem mad to think we can stop Nature’s law in this way. But to some, the opposite seems madder still: that all of this hope, wonder, memory and becoming will simply cease. And so the dream of an elixir that can preserve and prolong life is something close to a human universal, found in cultures across time and place. Stay alive, this dream whispers, day by day, and the years will take care of themselves.

Resurrection

In our struggle with the prospect of death, we seek sense-giving images from the world around us. “Do dead people come back again in the spring like flowers?” three-year-old Jane asked her mother. Well, Jane, wait until spring and we’ll see.

In nature, dying is not the end, but only part of a greater cycle — a cycle of life, death and rebirth. In contrast, a human life is linear: it progresses from birth through accretion then diminution into death and… that is it. The dead do not burst forth from the earth like March bluebells. At least, not when left to their own devices. But perhaps, we think, with a little help, these corpses can indeed be coaxed from the grave.

Magic, religion and science have long been united in the aim of transmuting the linear into the cyclical: transmuting that which is done and dust into that which re-forms and is re-done. So world religions are populated with dyingand- rising gods, from Osiris to Jesus, who serve as pioneers; who pass on to us the rituals — mummification, holy communion, cryonic freezing — that are to liberate us from linearity, that we might live again.

This is the hope of resurrection; a hope as humble as a bluebell and as grandiose as the gods.

Soul

It cannot be seen, or touched, or felt or smelt. It is undetectable, both in theory and practice. But we believe in it anyway. Even in our increasingly secular age, the vast majority of people on earth think they have a spiritual inner self. Few people, it seems, are happy to be soulless.

Perhaps it is because our bodies alone hardly seem adequate for the job of being human: messy and squelchy, prone to breakdown and destined for dissolution. How much better to believe that our real nature is something intrinsically indestructible, pure and immortal — a spark of the divine. When the body is lowered into the earth, we hope the soul will at the same time soar into the sky.

Of all the immortality beliefs, the soul most neatly answers the paradox at the heart of our view of death. On the one hand, we see that all things die and realise that we must too. But on the other hand, we cannot conceive of what this implies — our own non-existence; by simply trying to imagine the world without us, we conjure ourselves into being as the observing I/eye. And so death seems both inevitable and impossible. But for the ensouled, this is no problem at all: it is only my body that dies; I, the soul, fly free and forever. And so the paradox is resolved, and eternity ours. Or so the story goes.

Legacy

Most people fade from memory faster than we like to think: do you know the names of your eight great-grandparents? Only three generations gone and they have already evanesced like summer dew.

But this is not everybody’s fate. When Brad Pitt stormed the beach in the film Troy, clad in Achilles’ helmet and greaves, he was enacting his role’s greatest wish: everlasting glory. Achilles knew — because it had been prophesied — that if he stayed for the siege he would die, but that he would win undying fame. And so he stayed and fought and died and lives on. Ancient Greek warriors, like Hollywood actors, were in the immortality business.

But what life has Achilles won? Is he less dead because you are now reading his name? Less dead for all the films and statues he inspired? Or are those young men less dead whom he in turn inspired? Those who read as boys of the heroes of Troy and the glory of falling in a foreign field.

Homer, who in the Iliad granted Achilles his second life, later mocked it in the Odyssey. The hero Odysseus visits his old friend in Hades, only to be shocked by Achilles’s account of the dreary afterlife. Odysseus remonstrates — surely you, most renowned of all warriors, cannot regret having sacrificed long life for glory? Achilles replies, “I would rather work the soil as a serf to some landless impoverished peasant than be King of all these lifeless dead.”