In The Face of Death

Publication designed by MOTH

Publication contributor:

Elixir | Resurrection | Soul | Legacy

By Stephen Cave

Publication contributor:

Elixir | Resurrection | Soul | Legacy

By Stephen Cave

Elixir

We humans are the true mortals. Simpler, smaller-brained creatures are free of death — not because the Reaper will spare them, but because they do not have to live with the knowledge that he won’t. They live in joyful ignorance of the inevitable. Once the shark has passed, the fish is free of fear, for a while at least. But we are never free of the knowledge that all this will end.

Today more than ever, we are each our own greatest project: we self-actualise, self-fulfil, self-express. And what happens when time is up? Are prizes handed out and grades awarded for the most actualised self? No, the entries are all torn to pieces, whether masterpiece or scribble. No wonder then that we dream of holding ourselves together, of fighting back the dissolution brought by time, of stopping the decay and disappearance of all that we have striven to be.

It might seem mad to think we can stop Nature’s law in this way. But to some, the opposite seems madder still: that all of this hope, wonder, memory and becoming will simply cease. And so the dream of an elixir that can preserve and prolong life is something close to a human universal, found in cultures across time and place. Stay alive, this dream whispers, day by day, and the years will take care of themselves.

Resurrection

In our struggle with the prospect of death, we seek sense-giving images from the world around us. “Do dead people come back again in the spring like flowers?” three-year-old Jane asked her mother. Well, Jane, wait until spring and we’ll see.

In nature, dying is not the end, but only part of a greater cycle — a cycle of life, death and rebirth. In contrast, a human life is linear: it progresses from birth through accretion then diminution into death and… that is it. The dead do not burst forth from the earth like March bluebells. At least, not when left to their own devices. But perhaps, we think, with a little help, these corpses can indeed be coaxed from the grave.

Magic, religion and science have long been united in the aim of transmuting the linear into the cyclical: transmuting that which is done and dust into that which re-forms and is re-done. So world religions are populated with dyingand- rising gods, from Osiris to Jesus, who serve as pioneers; who pass on to us the rituals — mummification, holy communion, cryonic freezing — that are to liberate us from linearity, that we might live again.

This is the hope of resurrection; a hope as humble as a bluebell and as grandiose as the gods.

Soul

It cannot be seen, or touched, or felt or smelt. It is undetectable, both in theory and practice. But we believe in it anyway. Even in our increasingly secular age, the vast majority of people on earth think they have a spiritual inner self. Few people, it seems, are happy to be soulless.

Perhaps it is because our bodies alone hardly seem adequate for the job of being human: messy and squelchy, prone to breakdown and destined for dissolution. How much better to believe that our real nature is something intrinsically indestructible, pure and immortal — a spark of the divine. When the body is lowered into the earth, we hope the soul will at the same time soar into the sky.

Of all the immortality beliefs, the soul most neatly answers the paradox at the heart of our view of death. On the one hand, we see that all things die and realise that we must too. But on the other hand, we cannot conceive of what this implies — our own non-existence; by simply trying to imagine the world without us, we conjure ourselves into being as the observing I/eye. And so death seems both inevitable and impossible. But for the ensouled, this is no problem at all: it is only my body that dies; I, the soul, fly free and forever. And so the paradox is resolved, and eternity ours. Or so the story goes.

Legacy

Most people fade from memory faster than we like to think: do you know the names of your eight great-grandparents? Only three generations gone and they have already evanesced like summer dew.

But this is not everybody’s fate. When Brad Pitt stormed the beach in the film Troy, clad in Achilles’ helmet and greaves, he was enacting his role’s greatest wish: everlasting glory. Achilles knew — because it had been prophesied — that if he stayed for the siege he would die, but that he would win undying fame. And so he stayed and fought and died and lives on. Ancient Greek warriors, like Hollywood actors, were in the immortality business.

But what life has Achilles won? Is he less dead because you are now reading his name? Less dead for all the films and statues he inspired? Or are those young men less dead whom he in turn inspired? Those who read as boys of the heroes of Troy and the glory of falling in a foreign field.

Homer, who in the Iliad granted Achilles his second life, later mocked it in the Odyssey. The hero Odysseus visits his old friend in Hades, only to be shocked by Achilles’s account of the dreary afterlife. Odysseus remonstrates — surely you, most renowned of all warriors, cannot regret having sacrificed long life for glory? Achilles replies, “I would rather work the soil as a serf to some landless impoverished peasant than be King of all these lifeless dead.”

We humans are the true mortals. Simpler, smaller-brained creatures are free of death — not because the Reaper will spare them, but because they do not have to live with the knowledge that he won’t. They live in joyful ignorance of the inevitable. Once the shark has passed, the fish is free of fear, for a while at least. But we are never free of the knowledge that all this will end.

Today more than ever, we are each our own greatest project: we self-actualise, self-fulfil, self-express. And what happens when time is up? Are prizes handed out and grades awarded for the most actualised self? No, the entries are all torn to pieces, whether masterpiece or scribble. No wonder then that we dream of holding ourselves together, of fighting back the dissolution brought by time, of stopping the decay and disappearance of all that we have striven to be.

It might seem mad to think we can stop Nature’s law in this way. But to some, the opposite seems madder still: that all of this hope, wonder, memory and becoming will simply cease. And so the dream of an elixir that can preserve and prolong life is something close to a human universal, found in cultures across time and place. Stay alive, this dream whispers, day by day, and the years will take care of themselves.

Resurrection

In our struggle with the prospect of death, we seek sense-giving images from the world around us. “Do dead people come back again in the spring like flowers?” three-year-old Jane asked her mother. Well, Jane, wait until spring and we’ll see.

In nature, dying is not the end, but only part of a greater cycle — a cycle of life, death and rebirth. In contrast, a human life is linear: it progresses from birth through accretion then diminution into death and… that is it. The dead do not burst forth from the earth like March bluebells. At least, not when left to their own devices. But perhaps, we think, with a little help, these corpses can indeed be coaxed from the grave.

Magic, religion and science have long been united in the aim of transmuting the linear into the cyclical: transmuting that which is done and dust into that which re-forms and is re-done. So world religions are populated with dyingand- rising gods, from Osiris to Jesus, who serve as pioneers; who pass on to us the rituals — mummification, holy communion, cryonic freezing — that are to liberate us from linearity, that we might live again.

This is the hope of resurrection; a hope as humble as a bluebell and as grandiose as the gods.

Soul

It cannot be seen, or touched, or felt or smelt. It is undetectable, both in theory and practice. But we believe in it anyway. Even in our increasingly secular age, the vast majority of people on earth think they have a spiritual inner self. Few people, it seems, are happy to be soulless.

Perhaps it is because our bodies alone hardly seem adequate for the job of being human: messy and squelchy, prone to breakdown and destined for dissolution. How much better to believe that our real nature is something intrinsically indestructible, pure and immortal — a spark of the divine. When the body is lowered into the earth, we hope the soul will at the same time soar into the sky.

Of all the immortality beliefs, the soul most neatly answers the paradox at the heart of our view of death. On the one hand, we see that all things die and realise that we must too. But on the other hand, we cannot conceive of what this implies — our own non-existence; by simply trying to imagine the world without us, we conjure ourselves into being as the observing I/eye. And so death seems both inevitable and impossible. But for the ensouled, this is no problem at all: it is only my body that dies; I, the soul, fly free and forever. And so the paradox is resolved, and eternity ours. Or so the story goes.

Legacy

Most people fade from memory faster than we like to think: do you know the names of your eight great-grandparents? Only three generations gone and they have already evanesced like summer dew.

But this is not everybody’s fate. When Brad Pitt stormed the beach in the film Troy, clad in Achilles’ helmet and greaves, he was enacting his role’s greatest wish: everlasting glory. Achilles knew — because it had been prophesied — that if he stayed for the siege he would die, but that he would win undying fame. And so he stayed and fought and died and lives on. Ancient Greek warriors, like Hollywood actors, were in the immortality business.

But what life has Achilles won? Is he less dead because you are now reading his name? Less dead for all the films and statues he inspired? Or are those young men less dead whom he in turn inspired? Those who read as boys of the heroes of Troy and the glory of falling in a foreign field.

Homer, who in the Iliad granted Achilles his second life, later mocked it in the Odyssey. The hero Odysseus visits his old friend in Hades, only to be shocked by Achilles’s account of the dreary afterlife. Odysseus remonstrates — surely you, most renowned of all warriors, cannot regret having sacrificed long life for glory? Achilles replies, “I would rather work the soil as a serf to some landless impoverished peasant than be King of all these lifeless dead.”

Good Grief

Publication designed by MOTH

Publication contributor:

Dark Star

By Michael Petry

Publication contributor:

Dark Star

By Michael Petry

Dark Star

Why does winter come to mind, when one speaks of death?

Winter’s ground is full of seeds, which shoot on spring’s approach; but death’s ground is barren. Winter’s trees are pocked with buds, which leaf with sap and sun; but death’s trees are withered. Winter’s lake seems frozen over, but beneath its surface fish still swim; but death’s lake is ice, frozen to the core.

When death comes, then winter and all seasons die.

When death comes and dirt is piled over our coffin, we do not suffocate. When death comes and worms devour our flesh, we do not cry out. When death comes and snow piles upon our grave, we do not shiver. When death comes and trees blossom, we do not smell their scent. When death comes and flowers bloom, we do not see their colours. When death comes and harvest is gathered in, our corpse remains buried in the field.

Our only hope is excrement.

Perhaps our corpse will be eaten by a worm; and the worm by a bird; and the bird by a fox; and the fox dies and composts the soil; and the composted soil feeds an apple tree; and the apple tree bears fruit; and then someone takes a bite out of us, and we cleave to them, and briefly live again in a state of unknowing or atomic memory.

No god will come to save us. No god ever did.

No god made the world. No god loved the world. No god damned the world. No god saved the world. Except, of course, the god of stories told by parents to their children, about faith and hope and love. But children sense the truth. And so they cry at night because they fear the darkness whose name is death.

Children sense the truth because they’re not wise enough to believe the lies. They remain possessed by animal instincts. Like a puppy they fear death without knowledge of its magnitude. Neither know of the dangers that they face when crossing a street, or from a stranger, or even their own parents but they know death’s smell, the coldness of its hand and they fear to face it. They know better than to look death in the eye, they prefer to be surprised in the last second, prefer not to see it coming, prefer to gasp the last breath and expire.

Although death comes in an instant, fear of its coming can last a lifetime. The torturer knows this and so delays death’s approach, has it hover on the threshold, keeps it at bay, so that it might be preceded by terror and fear. But if you don’t wait for death, if it just happens, if death just happens, then all beginnings end at once.

Clench your fist, shout at the dark, scream at the night, turn on the lights, rip down the shades, burn down the house, stare at the sun, prick your finger, cover your head, hide in a closet, run to a cave, swim to an island, visit a temple, confess to a priest, libate to a god, give a coin to a ferryman.

Your fist is dust, your shout unheard, your scream no more, the lights are dimmed, the shades destroyed, your house burned down, the sun unlit, you feel no pain, all covers crumbled, the closet empty, the cavern endless, the island sunk, the temple rubble, the priest exposed, the god unworshipped. As for death, no amount of pleading will stop his boney tap upon your shoulder, and when you’ve crossed the Styx all is forgotten: name, breath, flesh, the pull of gravity on your bones, the pull of love on your heart.

Buy a puppy, steal a kitten, have a baby, eat spring lamb; pluck an apple, bite it slowly, eat its flesh and eat its core. Hold the moment in the now, not the ever receding past, or the fast approaching future. Hold this word, this text, this breath, this blink, this heartbeat, this pulse of blood to the head. In an hour you might be dead. A car crashed, a bus swerved, a cut turned sceptic, a fish bone lodged, a ladder slipped, a gas main leaked, a stabbing, a shooting or a violent brawl.

Now is all you can call your own. Not even a moment from now can be taken for granted, not even to the end of this line, for each moment could be your last.

So, play with the puppy, stroke the kitten, cherish your baby, and chew the spring lamb. But know that no kisses can deflect death’s mouth should it come for your breath. No moment of rapture in the arms of a lover, no drop of sweat or semen, no moment of fulfilment of being inside or taken by another, no tongue on hot flesh can prepare us for the cold to come. We cannot take the memory of a liaison with Apollo to the grave, Eros will not fly to our aid no matter that he has driven his arrow deep in our flesh, a swallow of Dionysus’ joy may muddle our thoughts and make time fly faster than the feet of Mercury, we may feel like we have been struck by Zeus’ bolt from the heavens when we look at our lover.

But remember their face, burn it into the very electrons of your mind, for in an instant, it will pass out, like all thoughts, and hopes, and loves and only if there is some warped sense of humour that rules the cosmos, will that image, that love, live on, in the movement of the stars.

Michael Petry 2018

Why does winter come to mind, when one speaks of death?

Winter’s ground is full of seeds, which shoot on spring’s approach; but death’s ground is barren. Winter’s trees are pocked with buds, which leaf with sap and sun; but death’s trees are withered. Winter’s lake seems frozen over, but beneath its surface fish still swim; but death’s lake is ice, frozen to the core.

When death comes, then winter and all seasons die.

When death comes and dirt is piled over our coffin, we do not suffocate. When death comes and worms devour our flesh, we do not cry out. When death comes and snow piles upon our grave, we do not shiver. When death comes and trees blossom, we do not smell their scent. When death comes and flowers bloom, we do not see their colours. When death comes and harvest is gathered in, our corpse remains buried in the field.

Our only hope is excrement.

Perhaps our corpse will be eaten by a worm; and the worm by a bird; and the bird by a fox; and the fox dies and composts the soil; and the composted soil feeds an apple tree; and the apple tree bears fruit; and then someone takes a bite out of us, and we cleave to them, and briefly live again in a state of unknowing or atomic memory.

No god will come to save us. No god ever did.

No god made the world. No god loved the world. No god damned the world. No god saved the world. Except, of course, the god of stories told by parents to their children, about faith and hope and love. But children sense the truth. And so they cry at night because they fear the darkness whose name is death.

Children sense the truth because they’re not wise enough to believe the lies. They remain possessed by animal instincts. Like a puppy they fear death without knowledge of its magnitude. Neither know of the dangers that they face when crossing a street, or from a stranger, or even their own parents but they know death’s smell, the coldness of its hand and they fear to face it. They know better than to look death in the eye, they prefer to be surprised in the last second, prefer not to see it coming, prefer to gasp the last breath and expire.

Although death comes in an instant, fear of its coming can last a lifetime. The torturer knows this and so delays death’s approach, has it hover on the threshold, keeps it at bay, so that it might be preceded by terror and fear. But if you don’t wait for death, if it just happens, if death just happens, then all beginnings end at once.

Clench your fist, shout at the dark, scream at the night, turn on the lights, rip down the shades, burn down the house, stare at the sun, prick your finger, cover your head, hide in a closet, run to a cave, swim to an island, visit a temple, confess to a priest, libate to a god, give a coin to a ferryman.

Your fist is dust, your shout unheard, your scream no more, the lights are dimmed, the shades destroyed, your house burned down, the sun unlit, you feel no pain, all covers crumbled, the closet empty, the cavern endless, the island sunk, the temple rubble, the priest exposed, the god unworshipped. As for death, no amount of pleading will stop his boney tap upon your shoulder, and when you’ve crossed the Styx all is forgotten: name, breath, flesh, the pull of gravity on your bones, the pull of love on your heart.

Buy a puppy, steal a kitten, have a baby, eat spring lamb; pluck an apple, bite it slowly, eat its flesh and eat its core. Hold the moment in the now, not the ever receding past, or the fast approaching future. Hold this word, this text, this breath, this blink, this heartbeat, this pulse of blood to the head. In an hour you might be dead. A car crashed, a bus swerved, a cut turned sceptic, a fish bone lodged, a ladder slipped, a gas main leaked, a stabbing, a shooting or a violent brawl.

Now is all you can call your own. Not even a moment from now can be taken for granted, not even to the end of this line, for each moment could be your last.

So, play with the puppy, stroke the kitten, cherish your baby, and chew the spring lamb. But know that no kisses can deflect death’s mouth should it come for your breath. No moment of rapture in the arms of a lover, no drop of sweat or semen, no moment of fulfilment of being inside or taken by another, no tongue on hot flesh can prepare us for the cold to come. We cannot take the memory of a liaison with Apollo to the grave, Eros will not fly to our aid no matter that he has driven his arrow deep in our flesh, a swallow of Dionysus’ joy may muddle our thoughts and make time fly faster than the feet of Mercury, we may feel like we have been struck by Zeus’ bolt from the heavens when we look at our lover.

But remember their face, burn it into the very electrons of your mind, for in an instant, it will pass out, like all thoughts, and hopes, and loves and only if there is some warped sense of humour that rules the cosmos, will that image, that love, live on, in the movement of the stars.

Michael Petry 2018

Stuff

Publication designed by MOTH

An Extra Place at the Table

Publication designed by MOTH

Publication contributors:

'Dining with the dead’

Dr Elsa Richardson

Experience Design at the End of Life

Clare Hearn

Publication contributors:

'Dining with the dead’

Dr Elsa Richardson

Experience Design at the End of Life

Clare Hearn

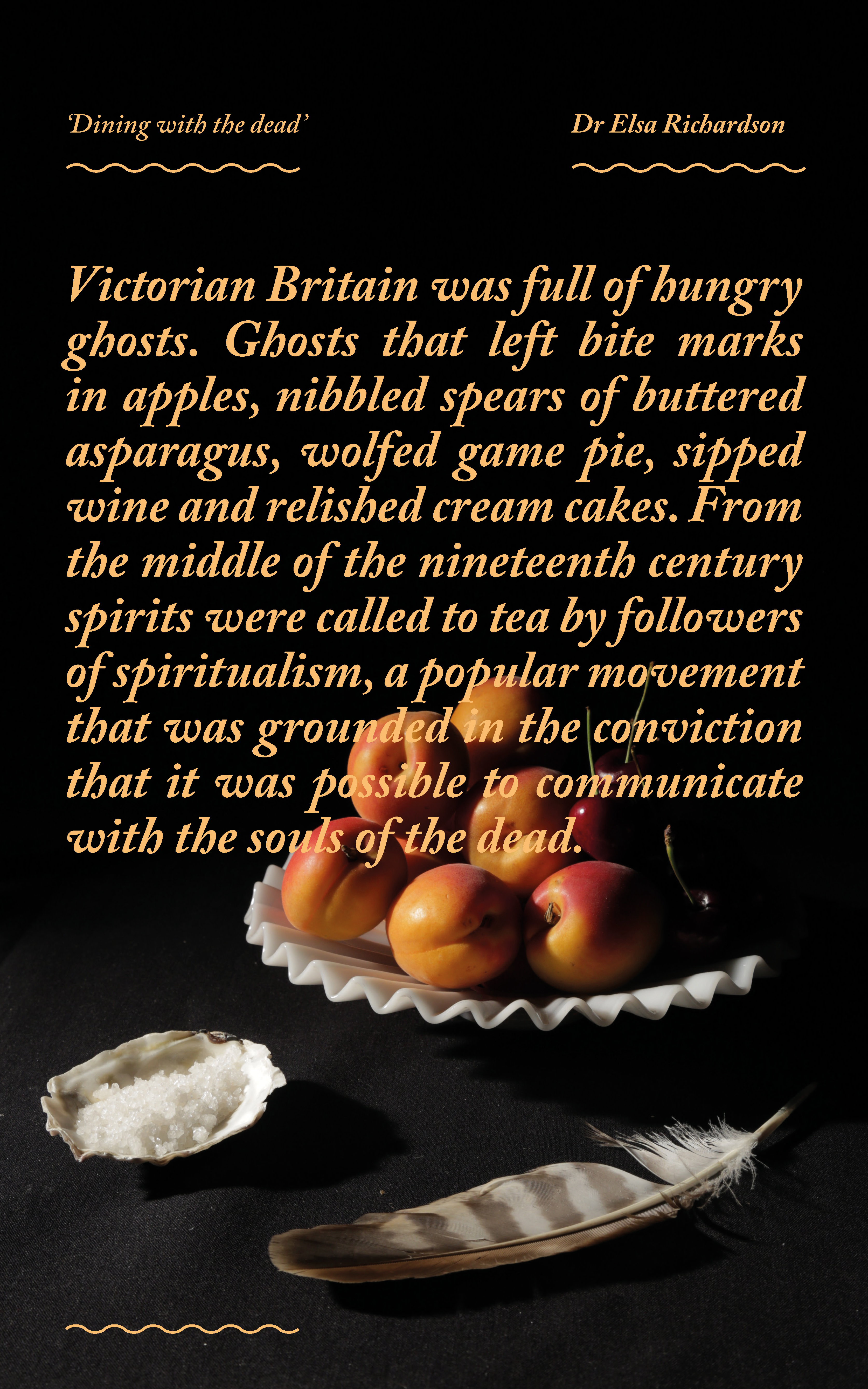

'Dining with the dead’

Dr Elsa Richardson

Writing in the 1960s, the structuralist anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss famously observed that ‘the cooking of any society is a kind of language which […] which says something about how that society feels about its relation to nation and culture’, and the history of spiritualism reveals that this observation could be easily extended into the afterlife.

Victorian Britain was full of hungry ghosts. Ghosts that left bite marks in apples, nibbled spears of buttered asparagus, wolfed game pie, sipped wine and relished cream cakes. From the middle of the nineteenth century spirits were called to tea by followers of spiritualism, a popular movement that was grounded in the conviction that it was possible to communicate with the souls of the dead. Originating in upstate New York, by the 1850s the so-called ‘spirit rapping craze’ had made its way across the Atlantic. Respectable dining rooms around the country played host to seances, during which furniture levitated, musical instruments played untouched, entranced women spoke with the tongues of famous dead men and clairvoyants described journeys to far-off realms. Spiritualism was, as the publisher James Burns insisted, a profoundly ‘domestic institution’ grounded in the morality of the home and the purity of the wives and daughters who presided over it. More complexly, though spiritualism allowed for an understanding of Victorian home as a sequestered space, removed from the amorality and bustle of the public world, the affective links established by the spirit circle also produced the domestic as a radically unbound site, open to otherworldly intervention and transformation.

In the enchanted domestic spaces produced by spiritualism, dining practices became essential to the practice of faith. Where in traditional Christian service, the consumption of food was controlled by the male clergy and confined to the taking of holy communion, in spiritualism food took on a more expansive and varied role. For one, it served an evangelical function: the lure of homemade cake and endless pots of tea promised by spiritualist associations drew many new believers to the cause, while domestic seances were usually accompanied by a spread of tempting sandwiches and savouries. Spiritualist accounts of the afterlife, what they described as the ‘Summerland’, often included descriptions of food and drink, and many of the questions put to visiting spirits concerned the issue of consumption. From reports given by spirits, the movement developed a remarkably detailed picture of what this ‘Summerland’ looked like: more than just a heaven of fluffy clouds and eternal love, the spiritualist afterlife was a whole other world, replete with alternative systems of governance, revised sexual relations and its own music, literature and art. This richly imagined world also necessitated a reconfiguration of the everyday and the domestic, a re-examination of quotidian habits: do we eat and drink in the afterlife? And if so what?

From the beginning, spiritualists blurred the line between séance and dinner. Sometimes a medium would request food from the spirits and with the lights dimmed, fruits would appear to cascade from the ceiling, as one hostess recorded in 1875 ‘flowers and ferns came down in great variety, followed by eight pears and seven apples. Tea being on the table, some partook of that and some of the fruit’. Food here becomes a means of crossing from the spiritual into the material, as the historian Marlene Tromp has observed ‘one of the most dazzling things the spirit could do was eat. If the spirit could chew, swallow and show evidence of teeth, it could prove both its presence and materiality beyond a doubt’. Beyond the corporeality of mastication and digestion, these otherworldly dining experiences were also social occasions. As with eating between the living, dining in the séance provided opportunities for connection, conversation and familiarity. What emerged from the spiritualist table was a disruptive version of middle-class dining, where etiquette gave way to ghostly intervention. A space in which the most female of duties – the preparation, serving and consumption of food – took on enchanted, erotic and sometimes subversive resonances.

Writing in his History of Spiritualism Arthur Conan Doyle described the need for a new religion, the collective longing that had brought about the advent of the spiritualist movement, in decidedly culinary terms: ‘The clergy’ he complained ‘are so limited in their ideas and so bound by a system which should be an obsolete one. It is like serving up last week’s dinner instead of having a new one. We want fresh spiritual food, not a hash of old food’. It is not surprising that Doyle would look to dining as a metaphor here, as food played a prominent and remarkably varied role within the spiritualist movement. Far more so than in traditional religious denominations, food was integral to the practice of spiritualism: the experience of shared dining helped to establish it as a domestic pursuit and to cement the role of women in the movement, while the materiality of food – the fruit that drops from dining room ceiling, the apple returned with unexplained bite marks – served as evidence of the close connection between this world and the next. Writing in the 1960s, the structuralist anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss famously observed that ‘the cooking of any society is a kind of language which […] which says something about how that society feels about its relation to nation and culture’, and the history of spiritualism reveals that this observation could be easily extended into the afterlife.

Experience Design at the End of Life

Clare Hearn

Food is often one of the core aspects of the ceremonial, of ritual events. Commensality, the sharing of meals, symbolizes and denotes social bonds and divisions, drawing boundaries between those who still eat together and those who do not.

In April, I spent a day delivering an undergraduate workshop on experience design to support the Death over Dinner Event element of Moth’s An Extra Place at the Table: Food and Funeral Feasting project.

The workshop manifest as a series of explorations, conceptual and practical, into theories and methods drawn from multiple disciplines. It was designed to both illuminate the nature of a new era of critical discourse about event experiences, their design, their meaning and their impact, and to consider how this can be utilized in the design of contexts for potentially deeply existential dialogue and thought.

Whilst this critical era of events scholarship is new, the study of events is not; they have been the object of scrutiny in a number of other disciplines for many years, most notably perhaps, social anthropology, in which the analysis of the events around death has long provided rich commentary on the meaning, structure and value within societies.

In recent years, events scholars have been pushing at the boundaries of what has been considered legitimate areas for research, with the result that event studies has become, for some at least, whatever the researcher wants it to be; it has, as Pernecky notes, become a site of ‘neutral territory, erected upon the ideals of epistemological freedom and academic creativity … [embracing] … disciplinary, multi-disciplinary, cross-disciplinary, inter-disciplinary, trans-disciplinary and post-disciplinary modes of inquiry’ (2016:4). From a new event studies perspective, consideration of how one might design experiences in which food and funeral feasting either enable dialogue on mourning, bereavement and end of life choices or which are themselves contexts for funeral feasting, must surely include establishment of an appropriate conceptual framework. However, 21st century event management professional practice has stood accused of having sacrificed awareness, understanding and inclusion of ritualistic elements in favour of artificially manufacturing events (Brown & James 2004).

In part therefore as a personal response, my research (and thus the workshop) explores experience design both practically, using management theory and activities to consider immersivity, inclusivity and co-creation methodologies but also conceptually, discussing the role of ritual, liminality and tradition in the design of funerary experiences, alongside nostalgia, authenticity, habitus, and of course, commensality.

At the time of writing, death research is experiencing a resurgence within international academia and industry. Recent studies have noted the increasing trend in Australia for a ‘deadly individualisation’ pervading the funeral in post-Christian societies, with collective rites replaced by personally tailored experiences focused solely on the individual (Singleton 2014).

The 2019 Global Wellness Trends Report named ‘Dying Well’ as its 8th trend, evidenced by research into the rise in popularity of ‘death doulas’, the ‘green burial wave’ and ‘death acceptance tourism’, all acts conducted in response to what author Beth McGroarty notes as our death denying society, fueled in part in the US by the Silicon Valley biotech industry aiming to cure death, and a pervasive ‘wellness’ agenda, a ‘21st century secular belief system …fundamentally directed at avoiding death anxiety…[by] convincing oneself that the right regimen of diet and exercise will keep you perpetually young or …perpetually alive’ (Soloman, cited in McGroarty 96: 2019).

The UK Competition and Markets Authority are conducting the second stage of their enquiry into the UK funeral industry, a hitherto unregulated sector, accused of opaque pricing at best and financial exploitation of the vulnerable at worst.

Such concerns are however, not without precedent. In 1963, Mitford’s The American Way of Death, a seminal text for the then nascent death awareness movement, accused the US funeral industry of profiteering by the selling of unnecessary services to the vulnerable bereaved.

In 21st century post-Christian secular societies, where discourse around death has been ‘privatized, secularized and medicalized’ (Simpson 7:2018), perhaps it is the role of experience designers and scholars to explore what new meaningful and performed rituals are needed in order to mark death. Szmigin & Canning suggest, when now bereaved, that we ‘are faced with situations often inherent in the social and/or cultural structure of the ritual that [we] find difficult, or which seem inappropriate or even anomalous to the personality or experience of the deceased or the mourners’ (749:2014). The loss of the accepted ritual experience of previous religious practices, which had served such a significant function in restoring a social fabric rent by loss, leaves us further bereft.

If we accept that funerary experiences provide (admittedly sometimes rejected) sites for collective acceptance of loss, where the dead are ‘reassembled, resurrected and regenerated in ways that are meaningful to those who have been left behind’ (Simpson 5:2018), how might we now need to design for these? As Wilson states, ‘the problem facing all who celebrate rituals in a fast-changing society is how to combine relevance to changing to changing circumstances with the sanctity of tradition’ (cited in Rothenbuhler 46:1998).

Currently, I suggest that the funeral is the only shared, least discussed and thus unplanned event within our experience economy (Pine and Gilmore 1999). It is the site of things which must be done (Mandelbaum 1959). But do we know what these things are? And by whom they should be done?

Anthropologist Arnold Van Gennap’s seminal work, The Rites of Passage, remains instructive. He observes that ‘changes of condition [deaths] do not occur without disturbing the life of society and the individual and it is the function of the rites of passage to reduce their harmful effects’ (13: 1960).

There persists a pervasive reluctance to openly engage with such existentially charged dialogue, despite the efforts of increasing numbers of communal initiatives, including Swiss sociologist Bernard Cretz’s Café Mortels, Jon Underwood‘s subsequent Death Cafés, and Hebb and Macklin’s Death over Dinner phenomenon.

Thus whilst growing numbers of ‘alternative’ funeral services appear, offering more simple, perhaps more ‘rational’ (as opposed to ‘religious’ or ‘superstitious’) experiences, including environmentally conscious options, these are still relatively rarely chosen; perhaps the notion of a ‘bare death’, relatively un-marked and thus un-mourned, still creates fear (Simpson 9:2018).

The notion of commensality, whilst core to the An Extra Place at the Table project, is not an automatic component in an exploration of experience design; however, in the context of the funeral experience, its relationship with ritual is essential. Food is often one of the core aspects of the ceremonial, of ritual events. Commensality, the sharing of meals, symbolizes and denotes social bonds and divisions, drawing boundaries between those who still eat together and those who do not.

For designers then, how might we reconcile the ‘deadly individualism’ of personalised rites of passage with the collective needs of those left behind to restore the integrity of social fabric through feasting and other rituals?

The funeral, an agreed space for mourning, can be deliberately designed to reflect current belief systems, to act as an essential boundaried transitional period, in which we can carefully move the dead into a socially collectively constructed mythologized narrative, enable survivors to experience separation communally, begin to darn the space left by death and start re-integration into society in its new form.

Through framing experience design with such concepts, enabling awareness, understanding and inclusion of ritualistic and other elements, we are far from providing Rojek’s ‘technocratic view of events, focus[ed] on the nuts and bolts in the machine and when and where to oil the parts’ (2013: xii).

We are instead creating and re-creating experiences, and, as Rothenbuhler comments, ‘rituals, like all social conventions, must be at some point be invented…’ (50:1998)

Bibliography

Andrews, H & Leopold, T (2013) Events and the Social Sciences Routledge: Oxon Bloch,

M & Parry, J (1982) Death and the Regeneration of Life Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

Brown, S. & James, J. Event design and management: ritual sacrifice? in Yeoman,

I et al Eds (2004) Festival and Events Management: An International Arts and Culture Perspective Amsterdam, The Netherlands; London: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann Gennap

Arnold van (1960) The Rites of Passage London: Routledge

Korsmeyer, Carolyn (2005) The Taste Culture Reader Oxford; New York: Berg Lupton,

Deborah (1996) Food, the Body and the Self London: Sage Mandelbaum

D. G. (1959) Social uses of funeral rites in H. Feifel (Ed.), The meaning of death. New York: McGraw-Hill McGroarty

B et al (2019) Global Wellness Trends 2019 Global Wellness Summit Metcalf

Peter & Huntington, Richard (1991) Celebrations of death : the anthropology of mortuary ritual Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Mitford, J (1963) The American Way of Death Simon & Schuster: New York Pine

J & Gilmore S (1999 and 2011) The Experience Economy Harvard Business Review Press: Boston Rojek, C (2013) Event Power: How Global Events Manage and Manipulate. London: Sage

Rothenbuhler, Eric. W (1998) Ritual communication Thousand Oaks, CA; London: Sage

Simpson, B. (2018) Death. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology (eds) F. Stein, S. Lazar, M. Candea, H. Diemberger, J. Robbins, A. Sanchez & R. Stasch

Singleton, A (2014) Religion, Culture and Society Sage: London Szmigin

I & Canning, L (2015) Sociological Ambivalence and Funeral Consumption in Sociology Vol: 49 (4) 748-763

Turner, V (1969) The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure Aldine de Gruyter: New York

Dr Elsa Richardson

Writing in the 1960s, the structuralist anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss famously observed that ‘the cooking of any society is a kind of language which […] which says something about how that society feels about its relation to nation and culture’, and the history of spiritualism reveals that this observation could be easily extended into the afterlife.

Victorian Britain was full of hungry ghosts. Ghosts that left bite marks in apples, nibbled spears of buttered asparagus, wolfed game pie, sipped wine and relished cream cakes. From the middle of the nineteenth century spirits were called to tea by followers of spiritualism, a popular movement that was grounded in the conviction that it was possible to communicate with the souls of the dead. Originating in upstate New York, by the 1850s the so-called ‘spirit rapping craze’ had made its way across the Atlantic. Respectable dining rooms around the country played host to seances, during which furniture levitated, musical instruments played untouched, entranced women spoke with the tongues of famous dead men and clairvoyants described journeys to far-off realms. Spiritualism was, as the publisher James Burns insisted, a profoundly ‘domestic institution’ grounded in the morality of the home and the purity of the wives and daughters who presided over it. More complexly, though spiritualism allowed for an understanding of Victorian home as a sequestered space, removed from the amorality and bustle of the public world, the affective links established by the spirit circle also produced the domestic as a radically unbound site, open to otherworldly intervention and transformation.

In the enchanted domestic spaces produced by spiritualism, dining practices became essential to the practice of faith. Where in traditional Christian service, the consumption of food was controlled by the male clergy and confined to the taking of holy communion, in spiritualism food took on a more expansive and varied role. For one, it served an evangelical function: the lure of homemade cake and endless pots of tea promised by spiritualist associations drew many new believers to the cause, while domestic seances were usually accompanied by a spread of tempting sandwiches and savouries. Spiritualist accounts of the afterlife, what they described as the ‘Summerland’, often included descriptions of food and drink, and many of the questions put to visiting spirits concerned the issue of consumption. From reports given by spirits, the movement developed a remarkably detailed picture of what this ‘Summerland’ looked like: more than just a heaven of fluffy clouds and eternal love, the spiritualist afterlife was a whole other world, replete with alternative systems of governance, revised sexual relations and its own music, literature and art. This richly imagined world also necessitated a reconfiguration of the everyday and the domestic, a re-examination of quotidian habits: do we eat and drink in the afterlife? And if so what?

From the beginning, spiritualists blurred the line between séance and dinner. Sometimes a medium would request food from the spirits and with the lights dimmed, fruits would appear to cascade from the ceiling, as one hostess recorded in 1875 ‘flowers and ferns came down in great variety, followed by eight pears and seven apples. Tea being on the table, some partook of that and some of the fruit’. Food here becomes a means of crossing from the spiritual into the material, as the historian Marlene Tromp has observed ‘one of the most dazzling things the spirit could do was eat. If the spirit could chew, swallow and show evidence of teeth, it could prove both its presence and materiality beyond a doubt’. Beyond the corporeality of mastication and digestion, these otherworldly dining experiences were also social occasions. As with eating between the living, dining in the séance provided opportunities for connection, conversation and familiarity. What emerged from the spiritualist table was a disruptive version of middle-class dining, where etiquette gave way to ghostly intervention. A space in which the most female of duties – the preparation, serving and consumption of food – took on enchanted, erotic and sometimes subversive resonances.

Writing in his History of Spiritualism Arthur Conan Doyle described the need for a new religion, the collective longing that had brought about the advent of the spiritualist movement, in decidedly culinary terms: ‘The clergy’ he complained ‘are so limited in their ideas and so bound by a system which should be an obsolete one. It is like serving up last week’s dinner instead of having a new one. We want fresh spiritual food, not a hash of old food’. It is not surprising that Doyle would look to dining as a metaphor here, as food played a prominent and remarkably varied role within the spiritualist movement. Far more so than in traditional religious denominations, food was integral to the practice of spiritualism: the experience of shared dining helped to establish it as a domestic pursuit and to cement the role of women in the movement, while the materiality of food – the fruit that drops from dining room ceiling, the apple returned with unexplained bite marks – served as evidence of the close connection between this world and the next. Writing in the 1960s, the structuralist anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss famously observed that ‘the cooking of any society is a kind of language which […] which says something about how that society feels about its relation to nation and culture’, and the history of spiritualism reveals that this observation could be easily extended into the afterlife.

Experience Design at the End of Life

Clare Hearn

Food is often one of the core aspects of the ceremonial, of ritual events. Commensality, the sharing of meals, symbolizes and denotes social bonds and divisions, drawing boundaries between those who still eat together and those who do not.

In April, I spent a day delivering an undergraduate workshop on experience design to support the Death over Dinner Event element of Moth’s An Extra Place at the Table: Food and Funeral Feasting project.

The workshop manifest as a series of explorations, conceptual and practical, into theories and methods drawn from multiple disciplines. It was designed to both illuminate the nature of a new era of critical discourse about event experiences, their design, their meaning and their impact, and to consider how this can be utilized in the design of contexts for potentially deeply existential dialogue and thought.

Whilst this critical era of events scholarship is new, the study of events is not; they have been the object of scrutiny in a number of other disciplines for many years, most notably perhaps, social anthropology, in which the analysis of the events around death has long provided rich commentary on the meaning, structure and value within societies.

In recent years, events scholars have been pushing at the boundaries of what has been considered legitimate areas for research, with the result that event studies has become, for some at least, whatever the researcher wants it to be; it has, as Pernecky notes, become a site of ‘neutral territory, erected upon the ideals of epistemological freedom and academic creativity … [embracing] … disciplinary, multi-disciplinary, cross-disciplinary, inter-disciplinary, trans-disciplinary and post-disciplinary modes of inquiry’ (2016:4). From a new event studies perspective, consideration of how one might design experiences in which food and funeral feasting either enable dialogue on mourning, bereavement and end of life choices or which are themselves contexts for funeral feasting, must surely include establishment of an appropriate conceptual framework. However, 21st century event management professional practice has stood accused of having sacrificed awareness, understanding and inclusion of ritualistic elements in favour of artificially manufacturing events (Brown & James 2004).

In part therefore as a personal response, my research (and thus the workshop) explores experience design both practically, using management theory and activities to consider immersivity, inclusivity and co-creation methodologies but also conceptually, discussing the role of ritual, liminality and tradition in the design of funerary experiences, alongside nostalgia, authenticity, habitus, and of course, commensality.

At the time of writing, death research is experiencing a resurgence within international academia and industry. Recent studies have noted the increasing trend in Australia for a ‘deadly individualisation’ pervading the funeral in post-Christian societies, with collective rites replaced by personally tailored experiences focused solely on the individual (Singleton 2014).

The 2019 Global Wellness Trends Report named ‘Dying Well’ as its 8th trend, evidenced by research into the rise in popularity of ‘death doulas’, the ‘green burial wave’ and ‘death acceptance tourism’, all acts conducted in response to what author Beth McGroarty notes as our death denying society, fueled in part in the US by the Silicon Valley biotech industry aiming to cure death, and a pervasive ‘wellness’ agenda, a ‘21st century secular belief system …fundamentally directed at avoiding death anxiety…[by] convincing oneself that the right regimen of diet and exercise will keep you perpetually young or …perpetually alive’ (Soloman, cited in McGroarty 96: 2019).

The UK Competition and Markets Authority are conducting the second stage of their enquiry into the UK funeral industry, a hitherto unregulated sector, accused of opaque pricing at best and financial exploitation of the vulnerable at worst.

Such concerns are however, not without precedent. In 1963, Mitford’s The American Way of Death, a seminal text for the then nascent death awareness movement, accused the US funeral industry of profiteering by the selling of unnecessary services to the vulnerable bereaved.

In 21st century post-Christian secular societies, where discourse around death has been ‘privatized, secularized and medicalized’ (Simpson 7:2018), perhaps it is the role of experience designers and scholars to explore what new meaningful and performed rituals are needed in order to mark death. Szmigin & Canning suggest, when now bereaved, that we ‘are faced with situations often inherent in the social and/or cultural structure of the ritual that [we] find difficult, or which seem inappropriate or even anomalous to the personality or experience of the deceased or the mourners’ (749:2014). The loss of the accepted ritual experience of previous religious practices, which had served such a significant function in restoring a social fabric rent by loss, leaves us further bereft.

If we accept that funerary experiences provide (admittedly sometimes rejected) sites for collective acceptance of loss, where the dead are ‘reassembled, resurrected and regenerated in ways that are meaningful to those who have been left behind’ (Simpson 5:2018), how might we now need to design for these? As Wilson states, ‘the problem facing all who celebrate rituals in a fast-changing society is how to combine relevance to changing to changing circumstances with the sanctity of tradition’ (cited in Rothenbuhler 46:1998).

Currently, I suggest that the funeral is the only shared, least discussed and thus unplanned event within our experience economy (Pine and Gilmore 1999). It is the site of things which must be done (Mandelbaum 1959). But do we know what these things are? And by whom they should be done?

Anthropologist Arnold Van Gennap’s seminal work, The Rites of Passage, remains instructive. He observes that ‘changes of condition [deaths] do not occur without disturbing the life of society and the individual and it is the function of the rites of passage to reduce their harmful effects’ (13: 1960).

There persists a pervasive reluctance to openly engage with such existentially charged dialogue, despite the efforts of increasing numbers of communal initiatives, including Swiss sociologist Bernard Cretz’s Café Mortels, Jon Underwood‘s subsequent Death Cafés, and Hebb and Macklin’s Death over Dinner phenomenon.

Thus whilst growing numbers of ‘alternative’ funeral services appear, offering more simple, perhaps more ‘rational’ (as opposed to ‘religious’ or ‘superstitious’) experiences, including environmentally conscious options, these are still relatively rarely chosen; perhaps the notion of a ‘bare death’, relatively un-marked and thus un-mourned, still creates fear (Simpson 9:2018).

The notion of commensality, whilst core to the An Extra Place at the Table project, is not an automatic component in an exploration of experience design; however, in the context of the funeral experience, its relationship with ritual is essential. Food is often one of the core aspects of the ceremonial, of ritual events. Commensality, the sharing of meals, symbolizes and denotes social bonds and divisions, drawing boundaries between those who still eat together and those who do not.

For designers then, how might we reconcile the ‘deadly individualism’ of personalised rites of passage with the collective needs of those left behind to restore the integrity of social fabric through feasting and other rituals?

The funeral, an agreed space for mourning, can be deliberately designed to reflect current belief systems, to act as an essential boundaried transitional period, in which we can carefully move the dead into a socially collectively constructed mythologized narrative, enable survivors to experience separation communally, begin to darn the space left by death and start re-integration into society in its new form.

Through framing experience design with such concepts, enabling awareness, understanding and inclusion of ritualistic and other elements, we are far from providing Rojek’s ‘technocratic view of events, focus[ed] on the nuts and bolts in the machine and when and where to oil the parts’ (2013: xii).

We are instead creating and re-creating experiences, and, as Rothenbuhler comments, ‘rituals, like all social conventions, must be at some point be invented…’ (50:1998)

Bibliography

Andrews, H & Leopold, T (2013) Events and the Social Sciences Routledge: Oxon Bloch,

M & Parry, J (1982) Death and the Regeneration of Life Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

Brown, S. & James, J. Event design and management: ritual sacrifice? in Yeoman,

I et al Eds (2004) Festival and Events Management: An International Arts and Culture Perspective Amsterdam, The Netherlands; London: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann Gennap

Arnold van (1960) The Rites of Passage London: Routledge

Korsmeyer, Carolyn (2005) The Taste Culture Reader Oxford; New York: Berg Lupton,

Deborah (1996) Food, the Body and the Self London: Sage Mandelbaum

D. G. (1959) Social uses of funeral rites in H. Feifel (Ed.), The meaning of death. New York: McGraw-Hill McGroarty

B et al (2019) Global Wellness Trends 2019 Global Wellness Summit Metcalf

Peter & Huntington, Richard (1991) Celebrations of death : the anthropology of mortuary ritual Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Mitford, J (1963) The American Way of Death Simon & Schuster: New York Pine

J & Gilmore S (1999 and 2011) The Experience Economy Harvard Business Review Press: Boston Rojek, C (2013) Event Power: How Global Events Manage and Manipulate. London: Sage

Rothenbuhler, Eric. W (1998) Ritual communication Thousand Oaks, CA; London: Sage

Simpson, B. (2018) Death. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology (eds) F. Stein, S. Lazar, M. Candea, H. Diemberger, J. Robbins, A. Sanchez & R. Stasch

Singleton, A (2014) Religion, Culture and Society Sage: London Szmigin

I & Canning, L (2015) Sociological Ambivalence and Funeral Consumption in Sociology Vol: 49 (4) 748-763

Turner, V (1969) The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure Aldine de Gruyter: New York

Four Deadlines & A Dinner

Publication designed by MOTH

Publication contributor:

The materiality of mourning: Representing grief through ordinary things.

By Anna Kiernan

Publication contributor:

The materiality of mourning: Representing grief through ordinary things.

By Anna Kiernan

Grief isn’t always about death. It’s often about memory. Memories that we cherish, memories that we go back to, memories that we wish we didn’t have burnt into our mind’s eye.

I am interested in grief both empirically and more abstractly. Through the projects I’ve worked on recently, which engage in some way with anticipated grief and memory, it seems that drawing on personal experience (whether it’s being discarded by a lover, or losing a loved one) can be a useful empathic starting point.

Remnants of lives, from archived objects to obituaries, are a rich source of stories. For me, in 2014, the notion of hidden histories prompted a desire to construct a small world of memory that was bound up with loss. I was keen to collaboratively explore ways in which objects and momentos could be seen as beneficial aids in the process of mourning.

In art, a very particular set of references and conventions come into play through momento mori. A basic momento mori painting might consist of a portrait with a skull, but other symbols include hour glasses or clocks, extinguished or guttering candles, fruit, and flowers. Artists from Pablo Picasso to Sarah Lucas and novelists from Muriel Spark and Max Porter all owe a debt to these metaphoric representations of death. Overtly symbolic in their depiction of time, life and decay, they function to represent life in the face of death as a series of objects.

‘Remember you must die’

Muriel Spark’s 1952 novel, Memento Mori is a darkly humorous exploration of memory and regret that’s captured by the eponymous concept of momento mori: ‘remember you must die.’ Max Porter’s 2016 novel Grief is the Thing With Feathers overlays an absurdist melancholy tale with a catalogue of seemingly irrelevant domestic remnants, creating an idiosyncratic version of momento mori.

Momento mori of a different kind can also be identified among the artefacts of those who may not have anticipated their own death and therefore the posthumous significance of their selected objects. ‘Abandoned Suitcases from an Insane Asylum’ is a powerful ethnographic account of how American society historically managed mental health. From the 1910s through the 1960s, many patients at the Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane left suitcases behind when they passed away. Upon the centre’s closure in 1995, hundreds of cases were found in a locked attic.

The idea of a life’s work being reduced to a suitcase of objects was so compelling to me that I decided to create my own momento mori as a miniature museum. The Museum of Momentos’ exhibited objects and photographs I had acquired and inherited, and was intended to explore the space between heritage and hoax, memory and meaning, nostalgia and loss.

Housed in a custom-made antique mahogany box for a large microscope, the museum was filled with, among other things, faded black and white photographs, a 1950s dolls pram and a cat’s skull. Hand-painted signs by artist Amy Goodwin invited the viewer to peruse the museum. An old-fashioned address box contained original typed poems that corresponded to the objects in the box, so that the viewer might follow a point of intrigue from the display to a poem, thought or fragment. Like the abandoned suitcases, the Museum of Momentos fitted into a box that could be closed and carried away, the stories and memories within it discreetly contained.

Grief is the Thing With Feathers

Two years later I came back to the idea of grief through a collaborative project with Ben James, Creative Director at Jotta. We won funding from the Cultural Capital Exchange to develop a VR narrative experience inspired by a literary text.

Around this time (2016), I came across a novel that felt right for the project and right in terms of its cultural significance beyond the project, namely Grief is The Thing With Feathers by Max Porter. The novel became a useful starting point for discussions around death and grieving in a project that, eventually, took on its own identity beyond the text.

In his review of Grief in the London Review of Books, Adam Mars-Jones echoes the publisher’s promotional tag that the text is a ‘polyphonic narrative’ (Mars-Jones, 2016). He suggests that, at times, ‘the dead woman’ (the mother who has died) is ‘not so much a person as a sustainer of a set of categories or symbolic properties, metaphysical sensations’:

‘Soft./ Slight./ Like light, like a child’s foot talcum-dusted and kissed, like stroke-reversing suede, like dust, like pins and needles, like a promise, like a curse, like seeds, like everything grained, plaited, linked or numbered, like everything nature-made and violent and quiet./ It is all completely missing. Nothing patient now.’ (Porter, 2015, p.18)

The density of emotional states alluded to in this passage reinforced our own sense of the inadequacy of reductive constructions of grieving. Drawing on Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ seminal text, ‘On death and Dying’, our early stages of research kept taking us back to models that rationalize extreme emotional states.

Kübler-Ross’ five stages of grieving are: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. The linearity of this model, while no doubt valuable in terms of managing difficult emotional states, may result in an expectation among those suffering from grief or extreme melancholia that is misleading. Put simply, the problem is one of assumed resolution. That after experiencing the first four stages of grief, the process is completed in the fifth stage.

Grief is The Thing With Feathers simultaneously interrupts and reinforces that assumption. Porter deploys narrative convention through several references to ‘Once upon a time’ (Porter, 2015, pp. 45, 71, 74, 77) but also toys with the notion. Written as an homage to Ted Hughes’ Crow, a viscerally powerful poetic response to loss, which, while delivering a blackly empathic account of negated interiority, refutes the possibility of closure.

The character of Crow in both Hughes’ and Porter’s texts is like a gently mocking god, omniscient and unpredictable. As Ben James noted in our correspondence around this project, in terms of the narrative flow, the veracity of Crow’s existence is immaterial since, whether he’s imaginary or real, the generative outcome is the same. Virtual spaces inhabit a similarly vague space and are able to coexist alongside ‘reality’. So while the landscape of Grief is populated with domestic objects that are documented in an encyclopedic way – in items listed, from toothpaste to turmeric – Crow’s presence is a sort of temporally stagnant palimpsest, mocking the simplistic assumption that time will heal, while simultaneously allowing (by drawing out the most brutal and absurd elements of grieving) time to heal.

‘And the memory fills all space’

This reading of crow formed the basis of the thinking behind our adaptation, in which ‘a permanent installation representing the ‘real’ could be installed alongside the VR element representing Crow. As such it could constitute an assemblage of objects or a magnified scene. The ‘real’ element could be performative as the twin narratives unfold – one in ‘reality’, one in virtual reality. The temporal framework for these dual narratives would serve as a critique of the notion of a linear understanding of the grieving process.

The materiality of mourning speaks volumes about grieving processes that are sometimes difficult to articulate through words or other coherent lexicons. Which is perhaps why an installation in an antique box or a VR project that exists beyond materiality, offer sites through which to explore the ideas of momento mori, memory and grief, from a range of perspectives and with open outcomes.

Book references:

Porter, M (2015), Grief is The Thing With Feathers. London: Faber.

Kübler-Ross, E (2008), On Death and Dying. London: Routledge.

Hughes, T (2001), Crow: From the Life and Songs of Crow. London: Faber.

Spark, M (2010), Memento Mori. London: Virago

Web references:

Felt, Daniel, Wired (7/11/15), ‘A VR Escape Room With a Twist: You’re Drunk’ in Wired: https://www.wired.com/2015/07/drunk-room-vr/ (Last accessed 2/7/17)

Mars-Jones, Adam (26/1/16), ‘Chop, chop, chop’ review of Grief is the Thing With Feathers in London Review of Books: https://www.lrb.co.uk/v38/n02/adam-mars-jones/chop-chop-chop(Last accessed 2/7/17)

http://jotta.com

I am interested in grief both empirically and more abstractly. Through the projects I’ve worked on recently, which engage in some way with anticipated grief and memory, it seems that drawing on personal experience (whether it’s being discarded by a lover, or losing a loved one) can be a useful empathic starting point.

Remnants of lives, from archived objects to obituaries, are a rich source of stories. For me, in 2014, the notion of hidden histories prompted a desire to construct a small world of memory that was bound up with loss. I was keen to collaboratively explore ways in which objects and momentos could be seen as beneficial aids in the process of mourning.

In art, a very particular set of references and conventions come into play through momento mori. A basic momento mori painting might consist of a portrait with a skull, but other symbols include hour glasses or clocks, extinguished or guttering candles, fruit, and flowers. Artists from Pablo Picasso to Sarah Lucas and novelists from Muriel Spark and Max Porter all owe a debt to these metaphoric representations of death. Overtly symbolic in their depiction of time, life and decay, they function to represent life in the face of death as a series of objects.

‘Remember you must die’

Muriel Spark’s 1952 novel, Memento Mori is a darkly humorous exploration of memory and regret that’s captured by the eponymous concept of momento mori: ‘remember you must die.’ Max Porter’s 2016 novel Grief is the Thing With Feathers overlays an absurdist melancholy tale with a catalogue of seemingly irrelevant domestic remnants, creating an idiosyncratic version of momento mori.

Momento mori of a different kind can also be identified among the artefacts of those who may not have anticipated their own death and therefore the posthumous significance of their selected objects. ‘Abandoned Suitcases from an Insane Asylum’ is a powerful ethnographic account of how American society historically managed mental health. From the 1910s through the 1960s, many patients at the Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane left suitcases behind when they passed away. Upon the centre’s closure in 1995, hundreds of cases were found in a locked attic.

The idea of a life’s work being reduced to a suitcase of objects was so compelling to me that I decided to create my own momento mori as a miniature museum. The Museum of Momentos’ exhibited objects and photographs I had acquired and inherited, and was intended to explore the space between heritage and hoax, memory and meaning, nostalgia and loss.

Housed in a custom-made antique mahogany box for a large microscope, the museum was filled with, among other things, faded black and white photographs, a 1950s dolls pram and a cat’s skull. Hand-painted signs by artist Amy Goodwin invited the viewer to peruse the museum. An old-fashioned address box contained original typed poems that corresponded to the objects in the box, so that the viewer might follow a point of intrigue from the display to a poem, thought or fragment. Like the abandoned suitcases, the Museum of Momentos fitted into a box that could be closed and carried away, the stories and memories within it discreetly contained.

Grief is the Thing With Feathers

Two years later I came back to the idea of grief through a collaborative project with Ben James, Creative Director at Jotta. We won funding from the Cultural Capital Exchange to develop a VR narrative experience inspired by a literary text.

Around this time (2016), I came across a novel that felt right for the project and right in terms of its cultural significance beyond the project, namely Grief is The Thing With Feathers by Max Porter. The novel became a useful starting point for discussions around death and grieving in a project that, eventually, took on its own identity beyond the text.

In his review of Grief in the London Review of Books, Adam Mars-Jones echoes the publisher’s promotional tag that the text is a ‘polyphonic narrative’ (Mars-Jones, 2016). He suggests that, at times, ‘the dead woman’ (the mother who has died) is ‘not so much a person as a sustainer of a set of categories or symbolic properties, metaphysical sensations’:

‘Soft./ Slight./ Like light, like a child’s foot talcum-dusted and kissed, like stroke-reversing suede, like dust, like pins and needles, like a promise, like a curse, like seeds, like everything grained, plaited, linked or numbered, like everything nature-made and violent and quiet./ It is all completely missing. Nothing patient now.’ (Porter, 2015, p.18)

The density of emotional states alluded to in this passage reinforced our own sense of the inadequacy of reductive constructions of grieving. Drawing on Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ seminal text, ‘On death and Dying’, our early stages of research kept taking us back to models that rationalize extreme emotional states.

Kübler-Ross’ five stages of grieving are: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. The linearity of this model, while no doubt valuable in terms of managing difficult emotional states, may result in an expectation among those suffering from grief or extreme melancholia that is misleading. Put simply, the problem is one of assumed resolution. That after experiencing the first four stages of grief, the process is completed in the fifth stage.

Grief is The Thing With Feathers simultaneously interrupts and reinforces that assumption. Porter deploys narrative convention through several references to ‘Once upon a time’ (Porter, 2015, pp. 45, 71, 74, 77) but also toys with the notion. Written as an homage to Ted Hughes’ Crow, a viscerally powerful poetic response to loss, which, while delivering a blackly empathic account of negated interiority, refutes the possibility of closure.

The character of Crow in both Hughes’ and Porter’s texts is like a gently mocking god, omniscient and unpredictable. As Ben James noted in our correspondence around this project, in terms of the narrative flow, the veracity of Crow’s existence is immaterial since, whether he’s imaginary or real, the generative outcome is the same. Virtual spaces inhabit a similarly vague space and are able to coexist alongside ‘reality’. So while the landscape of Grief is populated with domestic objects that are documented in an encyclopedic way – in items listed, from toothpaste to turmeric – Crow’s presence is a sort of temporally stagnant palimpsest, mocking the simplistic assumption that time will heal, while simultaneously allowing (by drawing out the most brutal and absurd elements of grieving) time to heal.

‘And the memory fills all space’

This reading of crow formed the basis of the thinking behind our adaptation, in which ‘a permanent installation representing the ‘real’ could be installed alongside the VR element representing Crow. As such it could constitute an assemblage of objects or a magnified scene. The ‘real’ element could be performative as the twin narratives unfold – one in ‘reality’, one in virtual reality. The temporal framework for these dual narratives would serve as a critique of the notion of a linear understanding of the grieving process.

The materiality of mourning speaks volumes about grieving processes that are sometimes difficult to articulate through words or other coherent lexicons. Which is perhaps why an installation in an antique box or a VR project that exists beyond materiality, offer sites through which to explore the ideas of momento mori, memory and grief, from a range of perspectives and with open outcomes.

Book references:

Porter, M (2015), Grief is The Thing With Feathers. London: Faber.

Kübler-Ross, E (2008), On Death and Dying. London: Routledge.

Hughes, T (2001), Crow: From the Life and Songs of Crow. London: Faber.

Spark, M (2010), Memento Mori. London: Virago

Web references:

Felt, Daniel, Wired (7/11/15), ‘A VR Escape Room With a Twist: You’re Drunk’ in Wired: https://www.wired.com/2015/07/drunk-room-vr/ (Last accessed 2/7/17)

Mars-Jones, Adam (26/1/16), ‘Chop, chop, chop’ review of Grief is the Thing With Feathers in London Review of Books: https://www.lrb.co.uk/v38/n02/adam-mars-jones/chop-chop-chop(Last accessed 2/7/17)

http://jotta.com